You have to give me credit for starting off with an easy subject, right? Aside from the nature of reality, there is probably no more argued and examined topic in the history of the world than the nature of evil. And that tells us something about it – that evil has been ingrained in the human psyche as long as there have been humans. The story of Cain and Abel is the archetypal example of this phenomenon – Cain murders his brother in order to strike back at God for favoring him, and in that sense, whatever you may believe about the Bible in general, it’s a true story.

The nature of truth is another one of those debated and contestable big questions which plague philosophers all their lives. What I mean by “true story” is that something in it, even if it’s a fictional story, rings true for the reader – there is an impact, because we recognize in the story something that is real, which makes the story memorable, and important enough to be transmitted. In that sense, the truest stories are frequently those from long ago, ancient stories which still exist today because there is something in them that is accurate about human nature. This is why mythical archetypes endure, and why superhero films are so popular today. They are the modern-day equivalent of the Greek myths – stories of super-powered gods battling monsters, sometimes in the literal sense in the case of characters like Thor. The fandoms of such stories (of which I am a member) frequently treat them as they would a religion, debating questions of canon and decrying heresy in the adaptations of their beloved characters. And with good reasons. Those who dismiss the rage of such fandoms are really missing the point of them. We are frequently derided as sad people with no lives, to be so obsessed with storytelling. But I’m a writer, so storytelling has to sort of obsess me since it’s my job. And the reason these stories and characters mean so much to people is because they represent a kind of emotional reality, however fantastical the setting. This is neatly summed up in Samwise Gamgee’s speech about “the stories that really mattered,” in the film version of The Two Towers: “Those were the stories that stayed with you, that meant something, even if you were too small to understand why.” His conclusion is that the moral of such stories is that there’s some good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for. And really, what could be truer than that? In order for a character and story to be appealing, something about them has to be truthful. Which brings me back to evil.

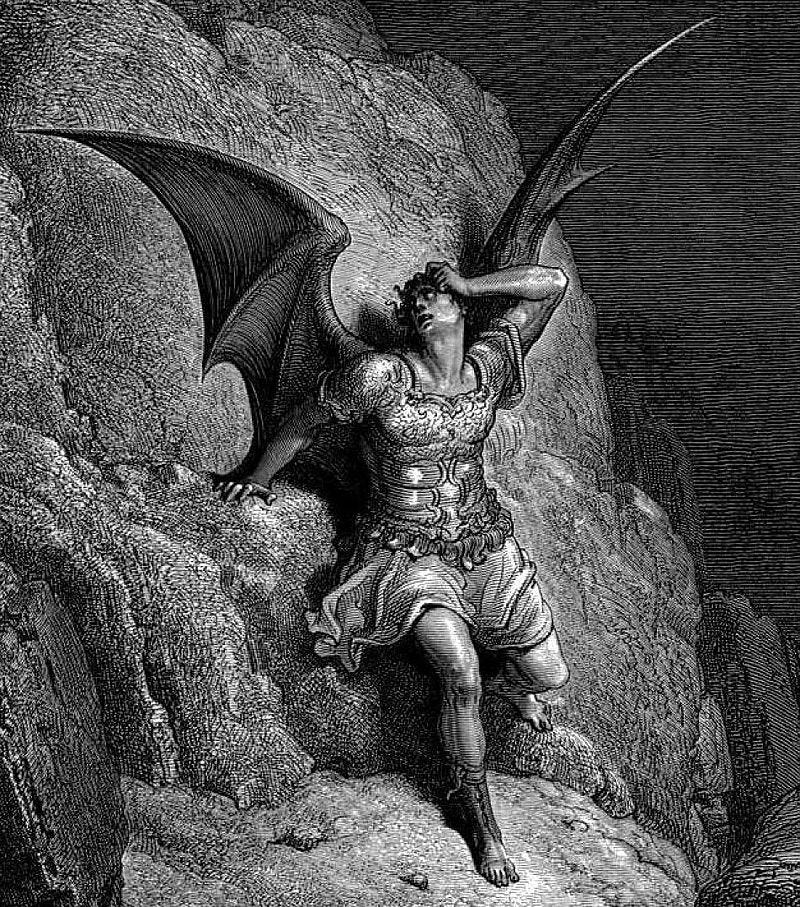

Cain and Abel is a true story because frequently evil is resentful and violent, striking out at established order and success whether from a sense of envy or bitter unfairness about the nature of reality. This is the archetypal villain, Satan himself, a proud angel believing he deserves more than to serve in heaven, and believes it’s better to reign in hell. Pride is probably the cardinal sin of evil – the belief that you know what’s best for everyone so you can tell them what to do. It’s why tyranny is evil, because the tyrant sees himself as having the right to control everyone around him – he believes he is uniquely suited for that role, because he is too proud to see otherwise.

In my early twenties, I was told by a peer that there was no such thing as real evil, and I believed it for a little while. Being raised atheist, I didn’t believe in Satan as such, and as with many people in their early twenties, I was interested in slaughtering the sacred cows of the past to make way for a bright, new future, which I was obviously enlightened enough to bring about in my early twenties. Evil, I thought, was really just based on your interpretation – morality was subjective, so how could anything be objectively wrong? This sort of thinking is typical in young people, and with age and experience, I saw the error of my ways. You can’t study the holocaust, for instance, without understanding only too well that evil exists, and what horrors it can inflict on innocent people.

We make excuses for evil the way I did as a young twentysomething – evil to one person may be good to another – it’s all based on your perspective. “One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter,” as the saying goes. Now obviously it’s true that some situations are more complex than black and white, but there are some situations where they’re really not. I think people everywhere can agree that the murder of children, say, is objectively evil. It’s why school shootings affect us all so badly – the idea that someone could take a gun and randomly murder kids is appallingly evil, to the extent that many people can’t understand it. It’s such an inhuman thing to do, and that’s the interesting thing about the nature of evil – we see it as something inhuman, when it’s actually a natural part of humanity, the shadow self that Jung speaks of, and that Solzhenitsyn says cuts through the heart of every human being. We all have the capacity for evil if properly motivated. People don’t like to think that, because they tend to see evil only as wanton violence. But not all evil is violent destruction. That’s the obvious kind of evil, the brutal dictator kind of evil. There’s a belief that people being cruel for the sake of cruelty is simplistic, but sadism is a real thing. Some people do enjoy inflicting pain and suffering on other people – it might be simplistic, but it’s not made up. But to my mind, the worst, most insidious kind of evil, which I have seen on the rise for the past few years, is evil disguising itself as good, pretending that tyranny and oppression can be for the greater good, and the benefit of humanity. And not always pretending – the most dangerous types sincerely believe it.

C.S. Lewis said about the nature of tyranny: “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron's cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience. They may be more likely to go to Heaven yet at the same time likelier to make a Hell of earth. This very kindness stings with intolerable insult. To be ‘cured’ against one's will and cured of states which we may not regard as disease is to be put on a level of those who have not yet reached the age of reason or those who never will; to be classed with infants, imbeciles, and domestic animals.”

This is absolutely the attitude of evil we see most commonly today – people who think they’re better and smarter than others, seeing them as particularly stupid children, and seeking to correct their evil, wrong thoughts. You saw this especially during COVID, when otherwise sane, rational people became fanatically obsessed with masks and lockdowns and vaccinations, and demanded that others follow their tyranny or be labeled as evil grandma killers. These were people on the self-proclaimed “right side of history,” which, as Lewis points out, makes it even worse, for they were doing evil with the approval not only of their own consciences, but of generations to come. But to coerce other people into acting against their will shows an arrogant belief in your own superiority of reason and morality – the sin of pride again being the apex of evil.

That’s why so many ancient stories warn of the nature of pride – hubris in Greek mythology. It’s one of the most common sins, perhaps the most human sin, but arguably the most dangerous sin. Because it is only pride which can lead humanity to act in inhuman ways, believing themselves to be superior to all others, to make themselves into the image of gods. And when we begin to worship ourselves as gods, bad things tend to happen. I think it would be beneficial for all of us to look into ourselves, examine our pride, and proclaim, “Not today, Satan.”