About a month ago, I watched the 1983 movie Scarface for the first time. I absolutely loved it, and while reading up about it afterward, I discovered it was a remake of an earlier movie also called Scarface from 1932. This movie was coincidentally on TCM the other week, so I made sure I caught it, because I wanted to compare and contrast the two versions – obviously I knew the 30s one would have much less explicit violence and much, much less swearing (the 80s Scarface script includes the word “fuck” 226 times). I knew that the 30s one was based on Al Capone, whose nickname was Scarface, so the character was an Italian immigrant rather than a Cuban one, and dealt in alcohol rather than cocaine. But obviously, those weren’t the only differences, or indeed similarities. Both versions were criticized when they were released for their explicitness, and their glorification of violence, because there really is nothing new under the sun.

TCM was running the 1932 Scarface as part of its Hays Gaze series, examining pre-code films and comparing them to post-code films. The Hays Code, or Motion Picture Production Code, was introduced in Hollywood in 1934 because of political pressure, and ensured that films contained no “unacceptable content” through 1968. I’m not a fan of censorship, except for children. Grown adults are mature enough to be able to judge things for themselves without a bunch of moralizing busybodies deciding what’s good for us. The upside of censorship is that creatives have to be clever to work around and outwit the censors, who aren’t very bright by definition – if they were bright, they wouldn’t be censors. One of my favorite shows, Batman: The Animated Series from 1992, had a long list of censorship demands (which is reasonable in children’s entertainment). But the writers very cleverly got around those by having the Joker’s toxin deform people with smiles instead of killing them, which was actually scarier, and having Harley talk about their sex life in innuendo (“Doncha wanna rev up your Harley?” “Wanna try some of my pie? I’m sure you’ll want seconds!”), which was funnier than it would have been if it was just explicit. So that’s a positive side effect of censorship, but I’m altogether against it on principle.

The major problem with censorship is that it doesn’t work. Telling people they shouldn’t see something makes people want to see it all the more. The very act of being censored increases the desire to taste this forbidden fruit, until being censored becomes a badge of honor. I’m reminded of Tipper Gore’s ill-advised crusade to put warning labels on music, because she wasn’t paying attention to what her children were listening to. I understand the desire to protect vulnerable children, but rather than encouraging censorship, we need to encourage good, active, engaged parenting. Parents are responsible for what their children see, and judging if they are mature enough to handle it. It is always a mistake to put any kind of external entity in charge of what we’re allowed to see and not see, because they will always abuse their power. Something introduced for the protection of children will usually end with adults being treated like children, and being judged too immature and vulnerable to be exposed to certain words or ideas.

This belief that adults have to be shielded from certain words and ideas is especially prevalent in our current times, under the guise of compassion, as tyranny usually is. We’re told we need “trigger warnings” in order to be kind, and to change old books in order to be inclusive. Rather than just treating the population like rational beings, the internet has given rise to citizen censors whose sole job (because I suspect they’re usually unemployed) is to find “problematic” material in some beloved piece of entertainment, and whine about it until it’s changed or a warning label is applied to it, usually with some groveling apology and condemnation of their earlier product (see Disney Plus and its pathetic warning labels on movies like The Aristocats – again, these measures are ostensibly for the protection of children, but in no sane world does a child need to be warned about The Aristocats.) It is the duty of any sane person, as it always is, to stand up to these petty tyrants and tell them not everyone is as mentally weak and fragile as they are, but we will be if they continue on this road.

To give these people the benefit of the doubt, many probably believe that they are being kind and inclusive, and preventing further damaging ideas from spreading. They probably believe in the blank slate theory of human nature, which nobody with a brain could believe in. But they probably believe if they can just get rid of all the bad words, then nobody will think bad things ever again, and there will be no more evil, and we can all live in harmony in some perfect utopia. Such is the purported reason behind “hate speech” laws, but to apply this to entertainment is to miss the point of entertainment and how we engage with it. For years, media effects theories have been trotted out as the reason behind mass shooters – video games like Doom were blamed for Columbine, and the fear of violence and the occult in horror films led to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. These theories actually go back much further, to the penny dreadful panic of the mid-19th century, where the mass appeal of stories featuring violence and gore were blamed for the rising crime rate.

The problem is that no direct correlation has ever been drawn between entertainment and real-world violence. Despite 60 years of study, no evidence has ever been found that entertainment influences behavior. Most people do not have a problem separating fiction from reality, and those that do should be kept away from violent imagery, but we shouldn’t ban violent imagery to placate a few people of unsound mind. Most people are of sound mind, and so censorship as a way of protecting people not only doesn’t work, it also patronizes people. And people resent being patronized.

The showing of the 1932 Scarface on TCM was followed by the post-code film The Roaring Twenties, made in 1939, which used clever tricks to get around the censorship demands of the time, such as presenting it in a documentary style. But what was interesting was to compare and contrast the portrayal of the central gangster figure in both – the Hays Code did not allow any sort of sympathy with criminals. And yet Scarface, which is pre-code, had a much less sympathetic gangster protagonist than The Roaring Twenties. Jimmy Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett was portrayed as having a conscience and a heart. His last act was to nobly sacrifice himself for the woman he loved in order to protect her family. Indeed, I was baffled as to why the woman did not return his love, since he clearly truly cared for her, and was much more of a dedicated, resolute character than the drippy man she ended up with. But then I’ve always had unusual taste in men.

I say that, but actually I’m not sure it’s true. The reason measures like the Hays Code were introduced was because censors didn’t want people to sympathize too much with the bad guys. They believed that people were so weak-minded that they would emulate any character they took a fancy to. This is obviously not true, but it’s something the censors desperately feared, and still fear to this day. I remember the media discourse when the 2019 movie Joker was released. I wasn’t a fan of the film at all, because the character portrayed isn’t the Joker, but I had no problem with its content. But I was genuinely shocked by how many people in the media were dreading, and almost hoping for a shooter to be inspired by it. There was a danger, they said, in romanticizing the Joker, which is one of the many reasons why we can’t have Harley and Joker together anymore. Many people don’t understand how Harley could love a man like that, but these people don’t have a very good imagination. The romantic outlaw character has existed from time immemorial in one form or another – gangster, pirate, rebels with a cause or without one. And these characters have always been considered very attractive by women.

Indeed, that was one of the differences between the two versions of Scarface that I thought was so intriguing. The 1932 version had both the women in Scarface’s life, his mistress and his sister, stand by him until the end. Even though he had just murdered her husband, his sister was there defending him during his final stand. The 1983 version also had his sister there, but she was trying to kill him, and his wife had abandoned him long before that. This despite the fact that the 1983 Scarface was a more noble character than the 1932 one – for instance, he marries his mistress in the 80s one, but not the 30s one. There is no scene in the 1932 one where Scarface refuses to murder children, as there is in the 1983 one, and it is this righteous act which brings about Scarface’s downfall in that version. And the 1932 Scarface surrenders to the police, putting his hands up and begging them not to shoot him, before making a break for it and getting shot. The 1983 one has Scarface going out in a blaze of glory, saying hello to his little friend, and fighting and firing until he can’t anymore. That’s certainly the more admirable ending to that character.

Now people have a real problem with the idea of a bad guy being admirable, but a good villain can be. You can hate what they do, but admire the way they do it. Indeed, the only villains I really hate are the ones who turn out to be cowards, like the 1932 Scarface. No matter how horrible they are, if they go out bravely meeting their end, I salute them. The contemptible characters are the cowardly ones, the non-entities. Jordan Peterson points this out from a Jungian perspective: “The mafioso villain types are at least courageous…and you could also point out, and this is sort of a comment on the necessity of integrating the Shadow, is that someone who’s forthright enough to be a mafioso at least isn’t terrified into dependent neuroticism. So there’s a hierarchy of virtue, and the forthright bad guy isn’t the lowest entity.” It’s why people like villains and anti-heroes – however bad they are, at least they’re not nothing. And a lot of women would prefer a courageous bad guy to a pathetic, emasculated nothing. This is also partly the appeal of heroic characters – while someone like Batman might not be a rational character, no one can question his bravery, and bravery is very appealing because it’s so rare in the real world. People brave enough to rush headlong into battle, heedless of the danger, is something that is in very short supply. Perhaps it is its rarity that makes it attractive.

And that’s why people like Scarface. He’s a horrible character, but he’s not a coward. He got what he wanted, even though he ended up destroying himself and everyone he cared about. Of course if this were real life, it would be better if he hadn’t done that, but in fiction, it’s an exciting story. And in terms of entertainment, an exciting story about a bad guy is better than a dull story where everyone is happy and virtuous. Stories are based on conflict, so the bigger the conflict, the better the story. And the better the character is at confronting the conflict, the better the character. Nobody can question Scarface’s willingness to fight. And from a purely instinctual, irrational perspective, that’s admirable.

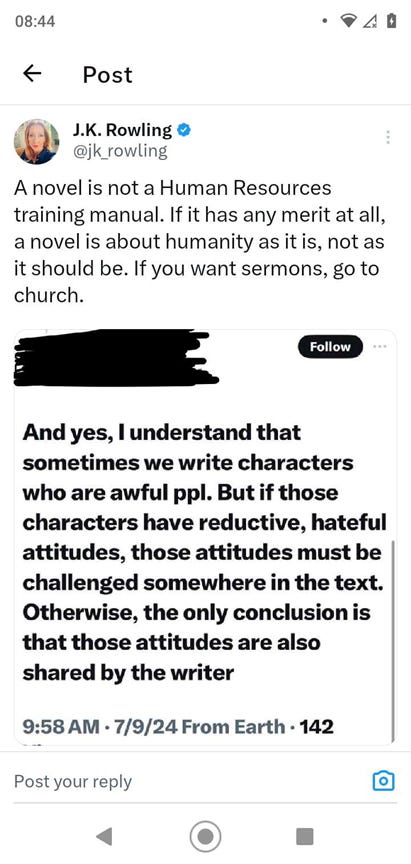

The other obvious point to make is that entertainment is not meant to be a guide to life, or an illustration of how life should be. J. K. Rowling pointed this out recently in response to a ridiculous tweet claiming that unless a book denounced a bad character at some point, the reader would assume that the author agrees with them. This is completely illiterate, as J. K. Rowling states: “A novel is not a Human Resources training manual. If it has any merit at all, a novel is about humanity as it is, not as it should be. If you want sermons, go to church.” As Oscar Wilde said in his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray way back in 1891: “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.” He also correctly concludes with: “Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art…We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.” Perhaps our modern day moralists could listen to him, and leave it the hell alone.